Five-Eighty is a novel about a private detective working in the suburbs of the Bay Area of California in the early 1970s. Each Saturday morning a new installment appears. As the events of this novel take place during the election season of 1974, the story will be released during this, the election season of 2024. May it prove an entertaining distraction from the news of the day. Please enjoy, and as always, comments are welcome!

—HF

Chapter 10

The next day is as gloomy as the last, a dank and sometimes drizzly day so that the cars that pass on Arlington up above the house make little spraying noises as they pass. Laura is already gone to work, her convertible top fixed in place on the Benz. I take the Volvo down to the Lucky’s on San Pablo to get miniature candy bars for Halloween. I really should have done this sooner, the selection is kind of picked over, it being the day before. There’s some Mars Bars, and candy corn, and that’s about it. Neither of us had time to make candy apples, though, and besides, we live in a world authored by Charlie Manson and the Symbionese Liberation Army. Nobody trusts home-made candy anymore.

Back at the house, I cart four paper bags worth of candy into the house, and as I set it down on the linoleum kitchen countertop, the phone rings. I pick it up, and it’s a lieutenant in the Oakland Police, wanting to come up to talk. I agree, and inside of an hour, I see through the front windows an unmarked pea-green Ford pulls up in front of the house and stops. The occupants are slow to get out, and slow to approach the house. One—the driver—is a tall black man with a short, tight head of hair and robust sideburns, wearing a coffee-colored plaid three-piece suit, the hem of its jacket bulging around where he keeps his sidearm. The passenger is a uniform, a white gym-rat type with a uniform that barely accommodated his overdeveloped body. They both let their eyes pass over everything on the way to the door, as if tourists, and as they draw closer, I see that the black man is younger, probably ten years below me, while the uniform is about my age, though his fine fair hair is beginning to gray at the temples.

I open the door for them.

“Mister Chisholm? Lieutenant-Detective DuPont, Oakland Pee-dee Homicide Division. This is Sergeant Folger, he works a West Oakland beat. May we come in?”

I wave them in. They step through, and again their heads swivel about them, as they stand in the foyer between the door and the glass partition.

“Is someone dead?” I ask.

“Hrm?” DuPont’s eyes come back to me. “No, no. Is there someplace we can sit and talk?”

I take them through the living room to the dining set that Laura had set up on the other side of the partition. DuPont picks a chair facing inward, and Folger sits on the same side, to his left, but cocked in his chair so he can turn his head to the left and look out at the view, if he wants. His eyebrows raise and he catches my glance. “Nice place you got here.”

“Thanks.” I sit in one of the chairs on the other side of the table, facing the two of them and the view of the bay. “Now how can I help you?”

DuPont starts. “Do you know a Helen Ritz?”

“Can’t say that I do.”

“Of… wait, where is it again, Sergeant?”

Folger reads off an address on Union Street.

“I’m not sure.”

DuPont shifts in his chair. “What do you mean, you’re not sure?”

“Can you describe her?”

Folger starts in, almost clinically, almost tired, reading off a small notepad he’s taken from a shirt pocket. “Five-foot-ten, brown skin, hair a mixture of gray and black…”

“A middle-aged black woman,” DuPont interjects. “Rather pretty for her age. Proud. Strong. Maybe not strong enough. Has a son named Isaiah, works as a bus mechanic for A.C. Transit.”

“Yes, I’ve met her once, and her son.”

“In connection with your job as a private investigator?”

“Yes, but I wasn’t investigating them.”

“When did you talk to them, and why?”

“Yesterday morning. I was trying to find the owner of a property, and the last registered address was on Union Street. I went to go see the owner, but they weren’t home, so I thought I’d talk to one of the neighbors and see if they knew anything. From your description I think Helen is the neighbor I talked to. Can you tell me what this is about? You said you’re from homicide, but also that nobody is dead.”

“Yesterday afternoon,” replies DuPont, “Missus Ritz went out for a walk, to go the corner store for her favorite vice, a pint of Dreyer’s. On the way home, she was stopped by two men. A witness says they talked to her, but they must not have liked what she said. They hit her. Missus Ritz must be a proud woman, ‘cause she took it, and she stood taller, and so they hit her again, only it went a little further than they probably had intended. She fell to the ground, hit her head, started bleeding on the sidewalk, passed out. The two men panicked, ran off. A dark red or maroon Lincoln was seen driving off at a fast clip not long after.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, will she be alright?”

“She’s at Kaiser. Doc says she’ll recover, but she’s got a concussion, and she’ll need time.”

“How did that all bring you to me?”

Folger: “We got called in. While she was unconscious, and we were waiting for the ambulance, we went through her purse looking for identification. We found your business card.” Folger pulled the card out from his notebook and slid it onto the table.

I nodded. “I gave both her and her son a card yesterday.”

“What for?” Asks DuPont.

“In case either of them remembered anything about their neighbors.”

“Why give them both cards?”

“I don’t think Isaiah liked me. I figured he might throw his away.”

“But Missus Ritz liked you?”

I shrugged. “A card is cheap, an opportunity isn’t.”

“Tell me more about your business, Mister Chisholm. As the sergeant said,” DuPont looks around the room with his head, making a show of it, then pursing his lips a little. “You have a nice place. How can you afford this on an investigator’s salary?”

“My wife’s family is in real estate, and the house was a wedding gift from my father-in-law.”

DuPont’s eyebrows go up. “Nice gift. Nice father-in-law. So you come from money, own real estate?”

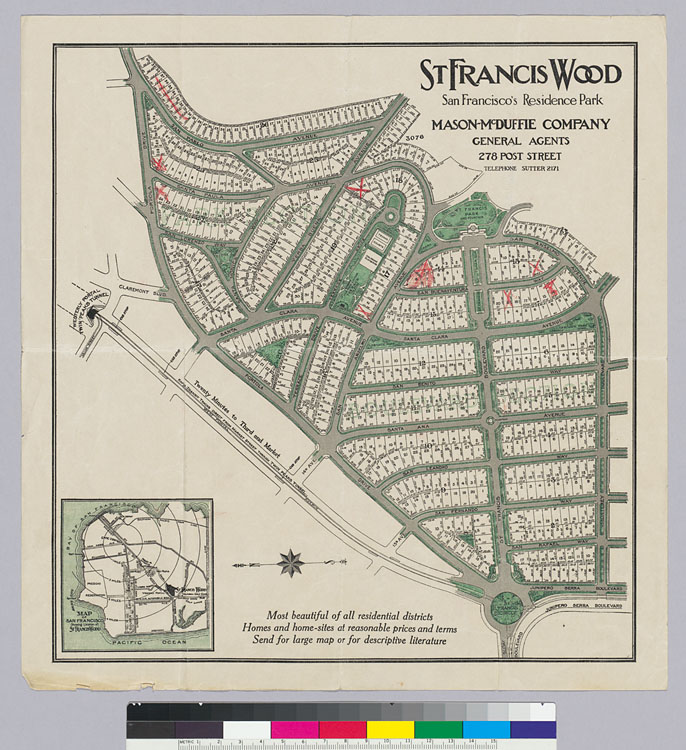

“No. Laura—my wife—is an estate agent. We own this, and we own a small office out in Santa Rita.”

“Still, not bad. But you aren’t an agent yourself?”

“No.”

“And you never finished your law degree.” DuPont’s eyes are cold, unmoving, locked on mine the way a big cat locks eyes on its prey.

I grin at him. “No. And I didn’t tell you I went to law school. So why don’t you tell me why you are really here?”

“I’m not sure what you mean.”

“You’ve done background research on me. It hasn’t even been twenty-four hours since Missus Ritz got put in the hospital. I think you’ve got ideas. Let’s hear them.”

DuPont shakes his head. “I’m just being thorough.”

“A black woman got beat up, maybe mugged, in West Oakland. And someone from the homicide division has taken the time to research me, then come up here with the beat cop who was on the scene, just to chat, just to be thorough. I don’t know much about criminal activity, at least not this wheelhouse of it, but none of that adds up.”

Folger: “And just what wheelhouse of criminal activity do you know about?”

“Theft. Fraud. Mostly theft. I specialize in property related disputes.”

Folger: “So what, you’re a repo man?”

“Yeah, sometimes.”

“Out collecting hammers and saws that didn’t get turned in by the Okies and Arkies some builder hired for the day?”

I crack a smile. “Yeah. Sometimes, if there’s enough hammers and saws missing. It can add up. But it’s also a bit missing persons, tracing down owners of trusts, defunct properties, finding people who owe on mechanic’s liens. That sort of thing.”

Folger is about to open his flap again, but I see DuPont hold up a hand at him, low near the table top. Then he takes a turn. “Mister Chisholm, forgive this question, but why?” I just cock an eyebrow, and he continues. “I mean, why do that kind of work? You have a nice house, apparently it’s all paid for. Your wife has a good job that brings in enough money to keep the place running. You may not have a law degree, but you’re pretty well educated. Most investigators are washed-out versions of us, people who couldn’t hack it in the force, or guys who retired then either couldn’t leave the game behind or wanted to make an extra buck.”

I just shrug as a response.

“Let’s move on. What was this property you were looking into yesterday?”

“A house up off Tunnel Road.”

“You got an address for it?”

I weigh this. On one hand, I could try and hold it back, but they already know that the property I’m looking at belongs to someone with an address next to the Ritz family, so the odds were high they could figure it out with enough legwork. I give up the address.

“And why did you want to find the owners of this property?”

“A client is interested in it, might want to buy it. It’s small, a modernist wood house, probably 1940s. Might be a Wurster, or maybe a Bernardi.”

“Wurster? Bernardi?”

“Architects. Specialized in a kind of relaxed blend of Modernist simplicity and California-inspired vernacular construction.”

I see Folger, who is taking notes in his small pad, frantically cross out something.

“And who were these owners?”

“It was a corporate owner, a company called Paris Holdings. According the to the Secretary of State’s office, the company has three directors, Frank Lions, Charles Maine, Louis Solaris.” Folger scribbled away. “All three listed that Union Street address as their home. Nobody was answering the door, though.”

“So you went next door to the neighbors.”

I nod. “And they hadn’t heard of any of them.”

“Well.” DuPont leans back in his chair, which I’d rather he wouldn’t do, since they must be antiques by now. “Seems like a dead end for you.”

“Until I went to the neighbor’s, yes.”

DuPont sits forward. “What did they tell you?”

“They’d never heard of any of those people. The son—Isaiah—told me that the house on Union belonged to some drug dealer or other. I’d never heard of him. Someone named French.”

Folger set his pencil down. DuPont, whose fingers were rapping the table off and on, froze.

DuPont: “Lenny French?”

“That’s the name.”

“Listen. You’ve gotten in over your head. Your client, whoever he is? Tell him to forget about that place in the hills. Find another property. Lenny French is a mean sonofabitch. It’s probably his guys who roughed up Missus Ritz. Be careful he doesn’t come after you next.”

“Why would he?”

“Same reason he came after Missus Ritz, I expect. To satisfy his curiosity. Besides, cruelty is a muscle. You’ve got to exercise it to keep it in shape.” DuPont looks at Folger. “You got anything else?”

“Nope.” Folger folds the notebook up and sticks it and his pencil into his shirt pocket. “I’m good.”

I walk them to the door, then out to the car. Dupont is about to get in when he pauses. “Hey, sarge.” Folger, who was getting into the car, steps back out behind the passenger side door. “Didn’t you say there was a maroon Lincoln that fled the scene of Missues Ritz’s altercation?”

“Yeah.”

DuPont nods forward with his chin. “Go check it out.”

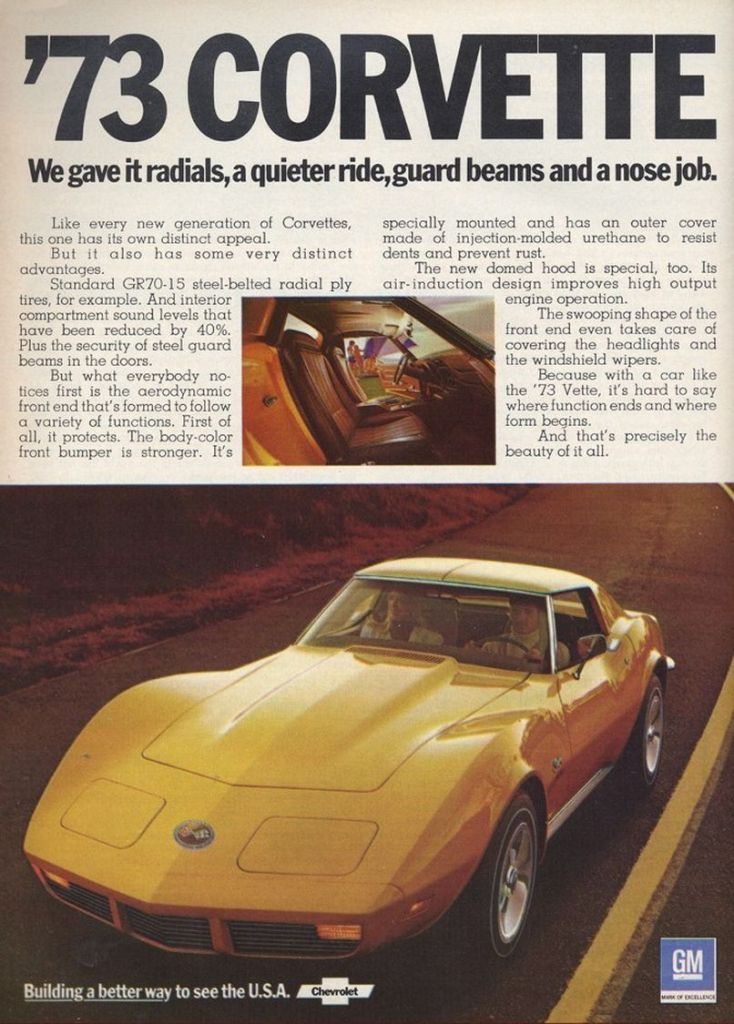

Looking up the road, on the left-hand side, there’s a Pontiac in baby blue, a little gold Honda, a gray Buick from twenty years ago, and behind it, facing the other way, a Continental in a color that might be red, or might be purple, or might be brown. Folger lets his door slide shut and starts walking up the sidewalk on the downhill side, approaching nice and slow. About halfway to his target, the tail lights on the Lincoln spring to life, and then the car pulls out into the lane and drives away. Folger gives an exaggerated “why me” shrug, then turns and starts walking back.

“Hey Lieutenant,” I say from across the top of the unmarked. DuPont looks across the roof at me. “You never said why a homicide cop would get stuck with this detail.”

“Mayor Reading is thinking about the next election. Having a couple white guys beat up a respectable old black lady? There’s no telling where that shit could end. He may have beat Bobby Seale last year, but losing 40% of the vote to a Black Panther isn’t exactly a comfortable place to be. Next time, it could be a brother who has appeal for the white vote, too, and then where is he?”

“But homicide?”

“No black folk in the red squad, and who else is he gonna send? Vice?”

Folger arrives back at the car.

“You get the plate?” DuPont asks.

“No, forgot my pencil in the house, and memory ain’t what it once was. Anyway hold on—” Folger turns to me. “Any chance I can get back in for my pencil?”

I lead him back to the house and open the door. He pushes past me fast, and by the time I get to the dining room table he’s already slipping his pencil in his shirt pocket. “Sorry about that. So hey, how’s your brother doing?”

“You know Nick?”

“Oh, yeah, we go way back.”

“He’s fine, just saw him yesterday.”

“Yesterday, huh? Well, what’s he doing for a living now, anyway?”

I shrug. “How do you know him?”

“Oh, we go way back.”

“You said that.”

“Yeah, I did.” We go back to the front door. In the door-jamb, Folger stops. “What the el-tee said, about leaving Lenny French alone? It’s good advice. And next time you see Nick, why don’t you tell him I said hello, huh?”

“Yeah, sure.”

“That’s good.” Folger began to move down the path to where the unmarked sits, running now, with DuPont behind the wheel smoking a cigarette and looking bored.

I raise a hand slightly. “Hey, sergeant.”

Folger pauses and looks back.

“You put the pencil in your pocket the first time you left. You had it on you when you walked down towards that Lincoln, and you know it.”

“Did I? I think you’re imagining things.”

Folger gets in the Ford, and the two of them leave.

More each Saturday!

Enjoy this installment of Five-Eighty? Watch for future installments every Saturday morning during Fall, 2024. The next intallment will post on Saturday, October 7th, 2024. Previous chapters can be viewed here.

A note about sharing. While this novel is released to the public free of charge, I reserve all rights to publication. You may send links to friends, post excerpts on social media, or share it in any reasonable way, but please do not repost whole chapters, nor print and distribute paper copies. Please also, whenever possible, share a link back to the content.